Skyhawk_310R

Charter Member

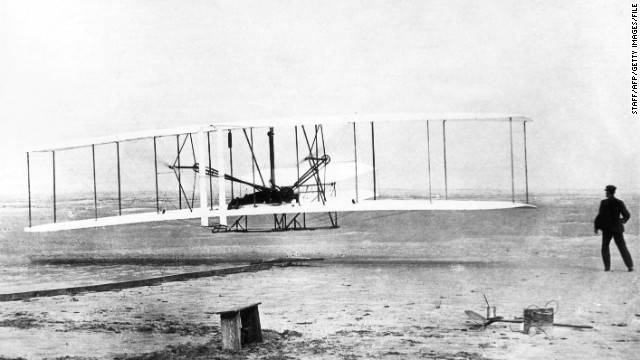

Not a particularly noteworthy day to write this, but sometimes that's not important. In recent days, despite the passing of well over 100 years since their achievement in 1903, the Wrights have again had their standing challenged by men with an ulterior motive. This is not new. In fact, among the more interesting aspects of this period from the first flight over Kitty Hawk, NC on December 17, 1903 and to 1908 when the Wrights demonstrated aircraft control well beyond what others could achieve, the Wrights were the victims of several underhanded efforts to write them out of history!

Samuel P. Langley provided the lynchpin for the first of these dirty tricks, but Langley was never a willing part of this. In fact, it really happened after the old man passed away. Langley was the secretary of the Smithsonian Institute at the time he pioneered the invention of what he called "the aerodrome." It's ironic that this term was later adopted to describe a base where planes took off and landed. Due to this coveted position, and his national respect, Langley received $50,000 in US government funding for his project. This put him light years ahead of other developers who were largely restrained by low funds and more family oriented support networks. It should also be added that others were pure charlatans who petitioned investors for their private money with the sole intent of pocketing the money and never producing anything capable of flight! This gave the age a hint of scandal wholly outside the control of legitimate inventors like Langley and the Wrights.

What the Wrights did that put them apart was their innovations of aircraft control, their rework of previously flawed mathematical models for airfoils, and their development of aircraft propellers. In fact, the Wrights received assistance from the Smithsonian so it must be added that Langley was a pure scientist who did not worry with competition and was perfectly willing to advance the science of aviation. The Wrights wrote the Smithsonian to ask for all the data they had and Langley's museum generously provided the Wrights with all they had! Unfortunately, this information ended up being more of a hindrance! Otto Lillienthal's pioneering mathematics for airfoils was proven entirely wrong by the Wright's glider tests!

This forced the Wrights to build their own wind tunnel, which ironically ended up being the state of the art for its time. They extensively tested airfoil shapes until they arrived at the most efficient shape, and along the way they mathematically developed entirely new models for airfoils which have withstood the passage of time. Then, they used the same wind tunnel to develop propellers that were 80% efficient back in 1903, which were only five percent less efficient than propellers manufactured today!

That would have been enough to cement their legacy, but they also pioneered the concepts of aircraft control, including consideration of the now classic three axis of aircraft control, pitch, yaw, and roll. They developed an intricate systems of cabling to facilitate wing warping to control roll. They used elevators and rudders to control pitch and yaw respectively. This was all pioneering both in concept and execution, and so the Wrights submitted a successful patent for all this technology with the US government. In these patents become the source of the intrigue.

From 1903 to 1906 the Wrights advanced their concepts on their Wright Flyer, and honed their pilot skills until they were able to astonish witnesses at airshows. While other pilots were barely able to maintain a straight line for a few hundred yards in ideal weather conditions, the Wrights were able to sustain flight for an hour, and perform a series of complex pattern work over the field, including figure-8's, box patterns, and turns about a pylon. In the course of their work, the Wrights also ended up become the two best pilots in the world.

But, by 1906, others were closing in as the opportunity for business success was undeniable. The Wrights also realized this and ended up tempering their public flight demonstrations until the US government finally awarded the brothers their patents on aircraft control and control systems. Glenn Curtiss wanted this technology, but did not want to pay the Wrights their legally entitled royalties to use their technology. So, Curtiss frankly stole it! The matter came to a legal head when Curtiss lost a famous patent lawsuit. Not satisfied to simply pay up and take his lumps, Curtiss hatched a rather strange and dishonorable action.

Curtiss worked with Langley's replacement as the new secretary of the Smithsonian, a man named Charles Walcott. Walcott, previously being Langley's understudy, did not take well to seeing Langley bested by the Wrights. While Langley himself was truly professional on the matter, Walcott certainly was not. Instead, he agreed to cooperate with Curtiss' idea, which was to gain unlimited access to Langley's aerodrome, copy it, and rework it as much as Curtiss needed to in order to get it into the air. Curtiss' goal was simple and undeniable. He hoped that by getting the aerodrome to fly, he could persuade the US government that this was a copy of the original aerodrome, vice a very significantly upgraded one, and therefore was capable of controlled and sustained flight. Curtiss then hoped to convince people that the Wright's patent was nullified since they really did not invent the means of aircraft control. In essence, Curtiss, having already lost a patent suit, wanted this stunt to be the means by which the Wrights would have their patent dishonored by the US government so that he could use the Wright's control systems without paying them any royalties. Curtiss also hoped to recover some of his lost respect having been humiliated in public in losing the Wright's patent suit.

With extensive rework, changes, and upgrades to the aerodrome, Curtiss was capable of making a flight that wasn't much better than what the Wrights had achieved with their 1903 Wright Flyer back in Kitty Hawk. The rub is that Curtiss achieved this flight in 1914, eleven years after the Wright Flyer's historic first flight! To term it an unfair and unprincipled effort would be a gross understatement! Yet, people today tend to regard the Wright's protection of their patents as bordering on paranoia. I would submit that when it is based upon fact it no longer can be considered to be paranoia!

Yet, under Walcott's direction, the Smithsonian ran wild with the results of Curtiss' flight. In the 1914 Smithsonian Report publication, A.F. Zahm went so far as to openly declare the aerodrome to be the "first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight." What a bold statement! Yet, that was the reality of the situation. The Smithsonian had literally declared open war on the Wrights, and along the way facilitated a corrupt effort by Glenn Curtiss to steal patented technology for his own personal enrichment. To this day, this represents a severe stain on the reputation of the Smithsonian Institute, and remains a source of righteous condemnation of Glenn Curtiss and Charles Walcott.

Things were made worse by the reality that in 1912, Wilbur Wright died of complications of typhoid fever. Whether justified or not, Orville Wright believed that his older brothers death was rooted in the extreme emotional anxiety caused by the withering patent fights not only fought with Curtiss, but with many other fledgling aircraft builders. Octave Chanute was instrumental in this widespread theft of the Wright's technology as he widely published the information for all to read and adopt. Chanute became friends with the Wrights in 1900, as they started their pioneering work. Chanute disagreed as a matter of philosophy with the Wright's patents for aircraft control, believing that the patent -- despite being legally issued -- was simply wrong. As a result, Chanute published everything without permission of the Wrights. This led to considerable friction between Chanute and the Wrights. Chanute's own words speak on the issue:

It would be fair to term Chanute's concerns to be a stand on scientific principle. But, for those who violated the Wright's standing patents, it was a far more monetary motivation. They simply wanted to use the technology without paying royalties to the Wrights.

Where this led was in hindsight almost unavoidable. Orville Wright concluded that the Smithsonian, under Walcott's control, had conspired with a rival to undermine the Wright's aircraft and aviation technology business. This mistrust was furthered by a total lack of cooperation by the US government, which shockingly refused, at least initially, to purchase any Wright Flyers. The government's concern was having been horribly burned by wasting $50,000 of investment capital in Langley's aerodrome work. This soiled the view of aircraft on the part of the US Army until several years later when the truth of the Wright Flyers success from European aircraft sales confirmed the worth of the Wright Flyer. The horrible reality is that the US government bet on the wrong horse and now, because of the pain of it, had suddenly fallen well behind European nations in aircraft technology! This would have profoundly negative consequences on America during World War I.

Given these two parallel developments, Orville Wright bestowed the 1903 Wright Flyer to London's South Kensington Science Museum. America's greatest gift to world aviation was sitting in honor in a British museum. The Smithsonian had officially asked for the Wright Flyer, but a bitter Orville Wright made his wishes very clear. He published that the 1903 Wright Flyer would remain in London until his death. Orville Wright also added a caveat about a change in this plan after his death. One frankly wonders how Charles Walcott could have looked himself in the mirror as he asked Orville Wright to move his airplane to the Smithsonian Institute!

Walcott died in 1928, and Charles Abbott was named secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. Abbott quickly worked to undo the damage done to both the Smithsonian and to the Wright's legacy. He published statements retracting those made in 1914. Unfortunately, Orville Wright considered those statement of Abbott, published in the 1928 Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, as too lukewarm in revising the very bold statements published in 1914. In short, it was not enough for Wright to reverse his desires and move the coveted 1903 Wright Flyer from London to Washington. In fairness, Abbott was in a corner. He wanted to repudiate what was done in 1914, but had political realities he had to account for. It is fair to say he did as much as he could at the time.

In 1942, Abbott went the full measure, asking aviation legend Charles Lindbergh to serve as an intermediary with the now aged Orville Wright. Further, Abbott published another paper in the same year that clearly repudiated the 1914 Faustian bargain made between Walcott and Curtiss. Abbott went further by making a very public apology and generous plea to Wright in the 1941 paper that read:

No one could have possibly written more magnanimous words, nor made a more heartfelt apology! Sadly, the bitterness of history was still too much for Orville Wright to publicly reverse course. Not even these efforts of Abbott and Lindbergh could achieve their desires while Wright was alive. But, unknown to any person, it did have an effect. Orville Wright changed his will, and that new will bequeathed the 1903 Wright Flyer to the Smithsonian Institute upon Wright's death. In 1948 the will was read, and the 1903 Wright Flyer was brought home, where it was indeed put in place as center of honor in the Smithsonian Institute Arts and Sciences building. It was not moved again until it was relocated in the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum.

Ken

Samuel P. Langley provided the lynchpin for the first of these dirty tricks, but Langley was never a willing part of this. In fact, it really happened after the old man passed away. Langley was the secretary of the Smithsonian Institute at the time he pioneered the invention of what he called "the aerodrome." It's ironic that this term was later adopted to describe a base where planes took off and landed. Due to this coveted position, and his national respect, Langley received $50,000 in US government funding for his project. This put him light years ahead of other developers who were largely restrained by low funds and more family oriented support networks. It should also be added that others were pure charlatans who petitioned investors for their private money with the sole intent of pocketing the money and never producing anything capable of flight! This gave the age a hint of scandal wholly outside the control of legitimate inventors like Langley and the Wrights.

What the Wrights did that put them apart was their innovations of aircraft control, their rework of previously flawed mathematical models for airfoils, and their development of aircraft propellers. In fact, the Wrights received assistance from the Smithsonian so it must be added that Langley was a pure scientist who did not worry with competition and was perfectly willing to advance the science of aviation. The Wrights wrote the Smithsonian to ask for all the data they had and Langley's museum generously provided the Wrights with all they had! Unfortunately, this information ended up being more of a hindrance! Otto Lillienthal's pioneering mathematics for airfoils was proven entirely wrong by the Wright's glider tests!

This forced the Wrights to build their own wind tunnel, which ironically ended up being the state of the art for its time. They extensively tested airfoil shapes until they arrived at the most efficient shape, and along the way they mathematically developed entirely new models for airfoils which have withstood the passage of time. Then, they used the same wind tunnel to develop propellers that were 80% efficient back in 1903, which were only five percent less efficient than propellers manufactured today!

That would have been enough to cement their legacy, but they also pioneered the concepts of aircraft control, including consideration of the now classic three axis of aircraft control, pitch, yaw, and roll. They developed an intricate systems of cabling to facilitate wing warping to control roll. They used elevators and rudders to control pitch and yaw respectively. This was all pioneering both in concept and execution, and so the Wrights submitted a successful patent for all this technology with the US government. In these patents become the source of the intrigue.

From 1903 to 1906 the Wrights advanced their concepts on their Wright Flyer, and honed their pilot skills until they were able to astonish witnesses at airshows. While other pilots were barely able to maintain a straight line for a few hundred yards in ideal weather conditions, the Wrights were able to sustain flight for an hour, and perform a series of complex pattern work over the field, including figure-8's, box patterns, and turns about a pylon. In the course of their work, the Wrights also ended up become the two best pilots in the world.

But, by 1906, others were closing in as the opportunity for business success was undeniable. The Wrights also realized this and ended up tempering their public flight demonstrations until the US government finally awarded the brothers their patents on aircraft control and control systems. Glenn Curtiss wanted this technology, but did not want to pay the Wrights their legally entitled royalties to use their technology. So, Curtiss frankly stole it! The matter came to a legal head when Curtiss lost a famous patent lawsuit. Not satisfied to simply pay up and take his lumps, Curtiss hatched a rather strange and dishonorable action.

Curtiss worked with Langley's replacement as the new secretary of the Smithsonian, a man named Charles Walcott. Walcott, previously being Langley's understudy, did not take well to seeing Langley bested by the Wrights. While Langley himself was truly professional on the matter, Walcott certainly was not. Instead, he agreed to cooperate with Curtiss' idea, which was to gain unlimited access to Langley's aerodrome, copy it, and rework it as much as Curtiss needed to in order to get it into the air. Curtiss' goal was simple and undeniable. He hoped that by getting the aerodrome to fly, he could persuade the US government that this was a copy of the original aerodrome, vice a very significantly upgraded one, and therefore was capable of controlled and sustained flight. Curtiss then hoped to convince people that the Wright's patent was nullified since they really did not invent the means of aircraft control. In essence, Curtiss, having already lost a patent suit, wanted this stunt to be the means by which the Wrights would have their patent dishonored by the US government so that he could use the Wright's control systems without paying them any royalties. Curtiss also hoped to recover some of his lost respect having been humiliated in public in losing the Wright's patent suit.

With extensive rework, changes, and upgrades to the aerodrome, Curtiss was capable of making a flight that wasn't much better than what the Wrights had achieved with their 1903 Wright Flyer back in Kitty Hawk. The rub is that Curtiss achieved this flight in 1914, eleven years after the Wright Flyer's historic first flight! To term it an unfair and unprincipled effort would be a gross understatement! Yet, people today tend to regard the Wright's protection of their patents as bordering on paranoia. I would submit that when it is based upon fact it no longer can be considered to be paranoia!

Yet, under Walcott's direction, the Smithsonian ran wild with the results of Curtiss' flight. In the 1914 Smithsonian Report publication, A.F. Zahm went so far as to openly declare the aerodrome to be the "first man-carrying aeroplane in the history of the world capable of sustained free flight." What a bold statement! Yet, that was the reality of the situation. The Smithsonian had literally declared open war on the Wrights, and along the way facilitated a corrupt effort by Glenn Curtiss to steal patented technology for his own personal enrichment. To this day, this represents a severe stain on the reputation of the Smithsonian Institute, and remains a source of righteous condemnation of Glenn Curtiss and Charles Walcott.

Things were made worse by the reality that in 1912, Wilbur Wright died of complications of typhoid fever. Whether justified or not, Orville Wright believed that his older brothers death was rooted in the extreme emotional anxiety caused by the withering patent fights not only fought with Curtiss, but with many other fledgling aircraft builders. Octave Chanute was instrumental in this widespread theft of the Wright's technology as he widely published the information for all to read and adopt. Chanute became friends with the Wrights in 1900, as they started their pioneering work. Chanute disagreed as a matter of philosophy with the Wright's patents for aircraft control, believing that the patent -- despite being legally issued -- was simply wrong. As a result, Chanute published everything without permission of the Wrights. This led to considerable friction between Chanute and the Wrights. Chanute's own words speak on the issue:

Octave Chanute said:I admire the Wrights. I feel friendly toward them for the marvels they have achieved; but you can easily gauge how I feel concerning their attitude at present by the remark I made to Wilbur Wright recently. I told him I was sorry to see they were suing other experimenters and abstaining from entering the contests and competitions in which other men are brilliantly winning laurels. I told him that in my opinion they are wasting valuable time over lawsuits which they ought to concentrate in their work. Personally, I do not think that the courts will hold that the principle underlying the warping tips can be patented.

It would be fair to term Chanute's concerns to be a stand on scientific principle. But, for those who violated the Wright's standing patents, it was a far more monetary motivation. They simply wanted to use the technology without paying royalties to the Wrights.

Where this led was in hindsight almost unavoidable. Orville Wright concluded that the Smithsonian, under Walcott's control, had conspired with a rival to undermine the Wright's aircraft and aviation technology business. This mistrust was furthered by a total lack of cooperation by the US government, which shockingly refused, at least initially, to purchase any Wright Flyers. The government's concern was having been horribly burned by wasting $50,000 of investment capital in Langley's aerodrome work. This soiled the view of aircraft on the part of the US Army until several years later when the truth of the Wright Flyers success from European aircraft sales confirmed the worth of the Wright Flyer. The horrible reality is that the US government bet on the wrong horse and now, because of the pain of it, had suddenly fallen well behind European nations in aircraft technology! This would have profoundly negative consequences on America during World War I.

Given these two parallel developments, Orville Wright bestowed the 1903 Wright Flyer to London's South Kensington Science Museum. America's greatest gift to world aviation was sitting in honor in a British museum. The Smithsonian had officially asked for the Wright Flyer, but a bitter Orville Wright made his wishes very clear. He published that the 1903 Wright Flyer would remain in London until his death. Orville Wright also added a caveat about a change in this plan after his death. One frankly wonders how Charles Walcott could have looked himself in the mirror as he asked Orville Wright to move his airplane to the Smithsonian Institute!

Walcott died in 1928, and Charles Abbott was named secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. Abbott quickly worked to undo the damage done to both the Smithsonian and to the Wright's legacy. He published statements retracting those made in 1914. Unfortunately, Orville Wright considered those statement of Abbott, published in the 1928 Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, as too lukewarm in revising the very bold statements published in 1914. In short, it was not enough for Wright to reverse his desires and move the coveted 1903 Wright Flyer from London to Washington. In fairness, Abbott was in a corner. He wanted to repudiate what was done in 1914, but had political realities he had to account for. It is fair to say he did as much as he could at the time.

In 1942, Abbott went the full measure, asking aviation legend Charles Lindbergh to serve as an intermediary with the now aged Orville Wright. Further, Abbott published another paper in the same year that clearly repudiated the 1914 Faustian bargain made between Walcott and Curtiss. Abbott went further by making a very public apology and generous plea to Wright in the 1941 paper that read:

Charles Abbott said:If the publication of this paper should clear the way for Dr. Wright to bring back to America the Kitty Hawk machine to which all the world awards first place, it will be a source of profound and enduring gratification to his countrymen everywhere. Should he decide to deposit the plane in the United State National Museum it would be given the highest place of honor, which is its due.

No one could have possibly written more magnanimous words, nor made a more heartfelt apology! Sadly, the bitterness of history was still too much for Orville Wright to publicly reverse course. Not even these efforts of Abbott and Lindbergh could achieve their desires while Wright was alive. But, unknown to any person, it did have an effect. Orville Wright changed his will, and that new will bequeathed the 1903 Wright Flyer to the Smithsonian Institute upon Wright's death. In 1948 the will was read, and the 1903 Wright Flyer was brought home, where it was indeed put in place as center of honor in the Smithsonian Institute Arts and Sciences building. It was not moved again until it was relocated in the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum.

Ken

Last edited: